Bricked Up

A story of personal loss in the face of ideology.

Shortly after I had moved to Belgrade, Serbia, I heard a story that grabbed me.

It was about how, during the Second World War, my wife’s grandfather and his brother had hidden their car from both the fascist Nazis and the communist Partisans.

They concealed it in a garage, which they then bricked up behind a false wall.

Before the outbreak of war, Branko and his brother Pera had enjoyed the bourgeois life that being a member of a well to do family entitled them to.

Their father owned a conglomerate of businesses linked to the real estate trade, and in the booming interwar years when Belgrade became the capital of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, business was good.

It was so good in fact that Branko and Pera, both of whom worked for their father, were able to buy one of the first privately owned cars in the city—a 1936 Studebaker.

Young men about town, Branko and Pera would wait for their strict and conservative father to fall asleep before pushing the car—engine off—down the street. Only once they knew to be well out of his earshot would they rev the engine and drive downtown to the thrills of the city’s nightlife.

This car was their youth, their freedom.

Yet these good times were not to last.

Spring of 1941

After a coup d’état against the Yugoslav Prince Paul frustrated Hitler’s plans in the Balkans, he vengefully ordered the destruction of Yugoslavia.

Branko and Pera got their mobilisation orders from the Royal Yugoslav Army and were sent several hundred kilometres away in an attempt to protect the borders against the imminent onslaught.

Neither they, nor the rest of the Yugoslav Army, ever stood a chance. The Yugoslavs signed an unconditional surrender on the 17th of April 1941.

Like thousands of others in their predicament, Branko and Pera now had to make the perilous way back home; by foot and mostly at night to avoid being captured by the occupying German forces.

By the time they made it back to Belgrade sometime in the summer of ‘41, they found a city gutted by a devastating Luftwaffe bombing campaign.

At home, they found that the family’s various businesses were shut down; no-one wanted to work for the occupiers.

Life under occupation

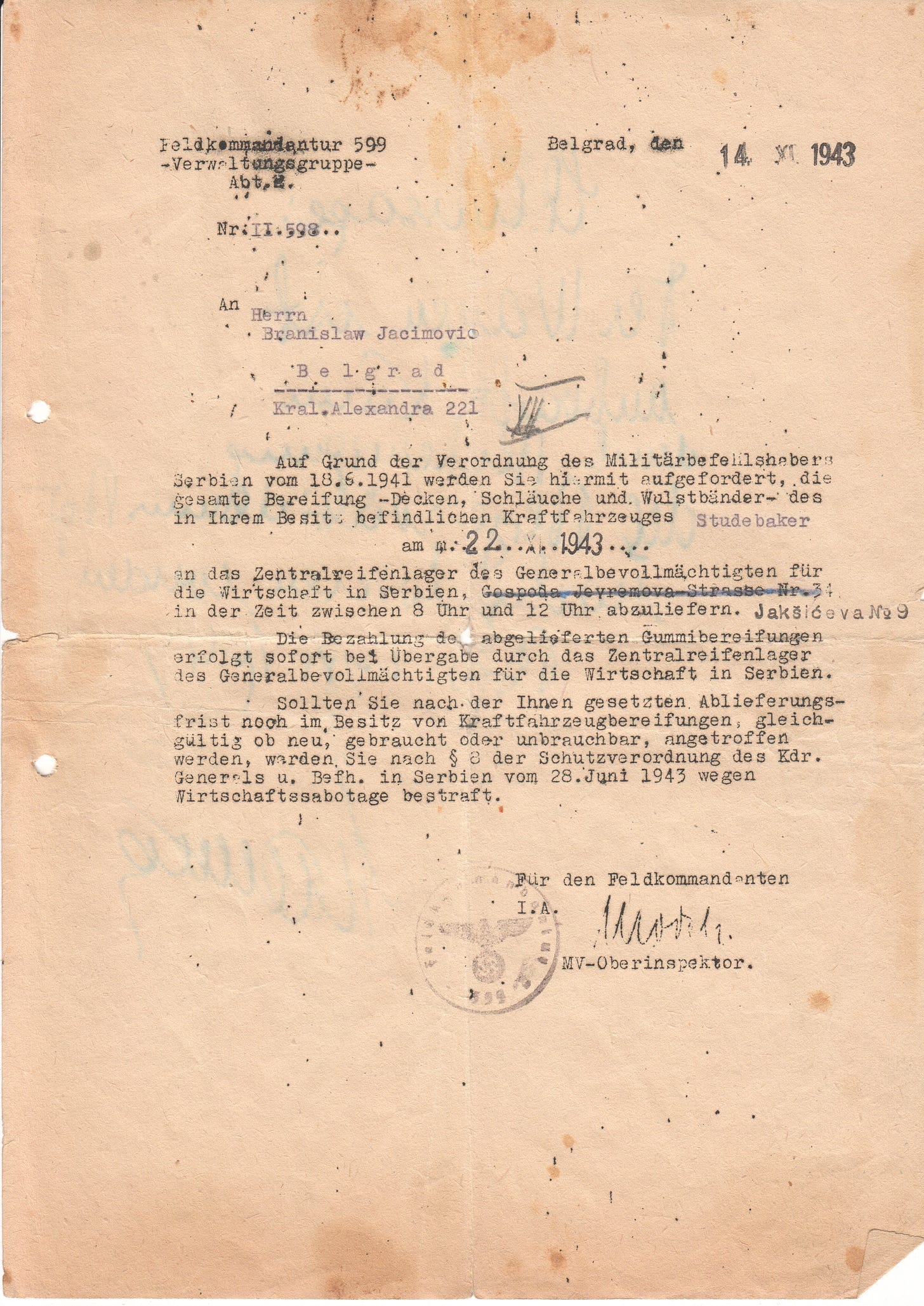

Very quickly, the German military command brought the efficiency of its administration to bear on all aspects of occupied life.

Two months after the invasion, for example, the German Military Governor of Serbia, General Ludwig von Schröder, issued an order that all rubber tyres of private vehicles be turned over to his military administration.

It’s here that family stories differ in details.

But it seems that Branko and Pera took the tyres off of the Studebaker and — in, perhaps, a small act of rebellion — hid them.

What’s certain is that shortly thereafter, the military administration informed Branko that:

“Your vehicle, newly registered under the number I–941, brand Studebaker, motor number B–13313, is hereby confiscated. You are not allowed to remove the vehicle from its current position.

Any further use, sale or removal of the vehicle, partly or completely, as well as the removal of equipment or spare parts is forbidden under punishment.

You will receive information concerning the use of the vehicle soon.

If you should not follow this order immediately, the vehicle will be commandeered by the German Armed Forces without compensation.”

By this stage, Yugoslavia was in the throes of a brutal three-way war between the fascist Nazis, the communist Partisans and royalist Chetniks.

Spurred on by their own ideologies and thirst for power, the fighting was characterised by varying degrees of changing and, at times, contradictory, alliances.

Fall of 1943

In time, this quagmire slowly began to turn against the Nazis. Not only had their Italian allies capitulated, the Germans had failed in every major offensive to wipe the Partisans out.

Impressed by the Partisan’s doggedness, the Allies used this pretext to overtly support them to the detriment of the Chetniks as the sole resistance movement.

A bloody civil war between the communist Partisans and the royalist Chetniks ensued.

Perhaps as a result of the German military’s growing impatience towards the situation, the military administration hardened its rhetoric towards the Serbian population.

Branko was again issued with an order to hand over any car tyres in his possession, and this time words were not minced:

“If you are caught while being still in possession of vehicle tyres, regardless of being new, used or unusable, after the delivery period, you will be prosecuted by §8 of the protection order of the Commanding Generals and the Military Governor of Serbia because of economical sabotage.”

As Branko and Pera’s pre-war life disappeared further from view in this thickening fog of war, they decided to hide as many traces of it as they could.

They hid the Studebaker in a garage, and bricked it up.

A liberated city

A year passed in this fashion until a combined push by Soviet and Partisan forces retook Belgrade in October of 1944.

Smelling a final victory, the ranks of the Partisans had by now swelled to 800,000 men and women from all over Yugoslavia, each adorning a five-pointed red star on their caps.

Branko too became one of them—he was mobilised yet again, this time as a truck driver. He was ordered to join the chase after the Nazis and their collaborators on their final retreat towards Austria.

Pera, for his part, somehow managed to avoid the last throes of war; in the newly liberated Belgrade, he took the Studebaker out from its hiding place and refitted it with its tyres.

Almost instantly, as the family story goes, an old friend who had since become an agent of the secret police, commandeered it ‘for the purposes of the state’.

A brave new world

By May of 1945, the war was over. Demobilised yet again, Branko returned home. He once again found a new order, only this time it was based on Brotherhood and Unity.

The communists were now in power and the symbol of his pre-war life, his Studebaker, was gone.

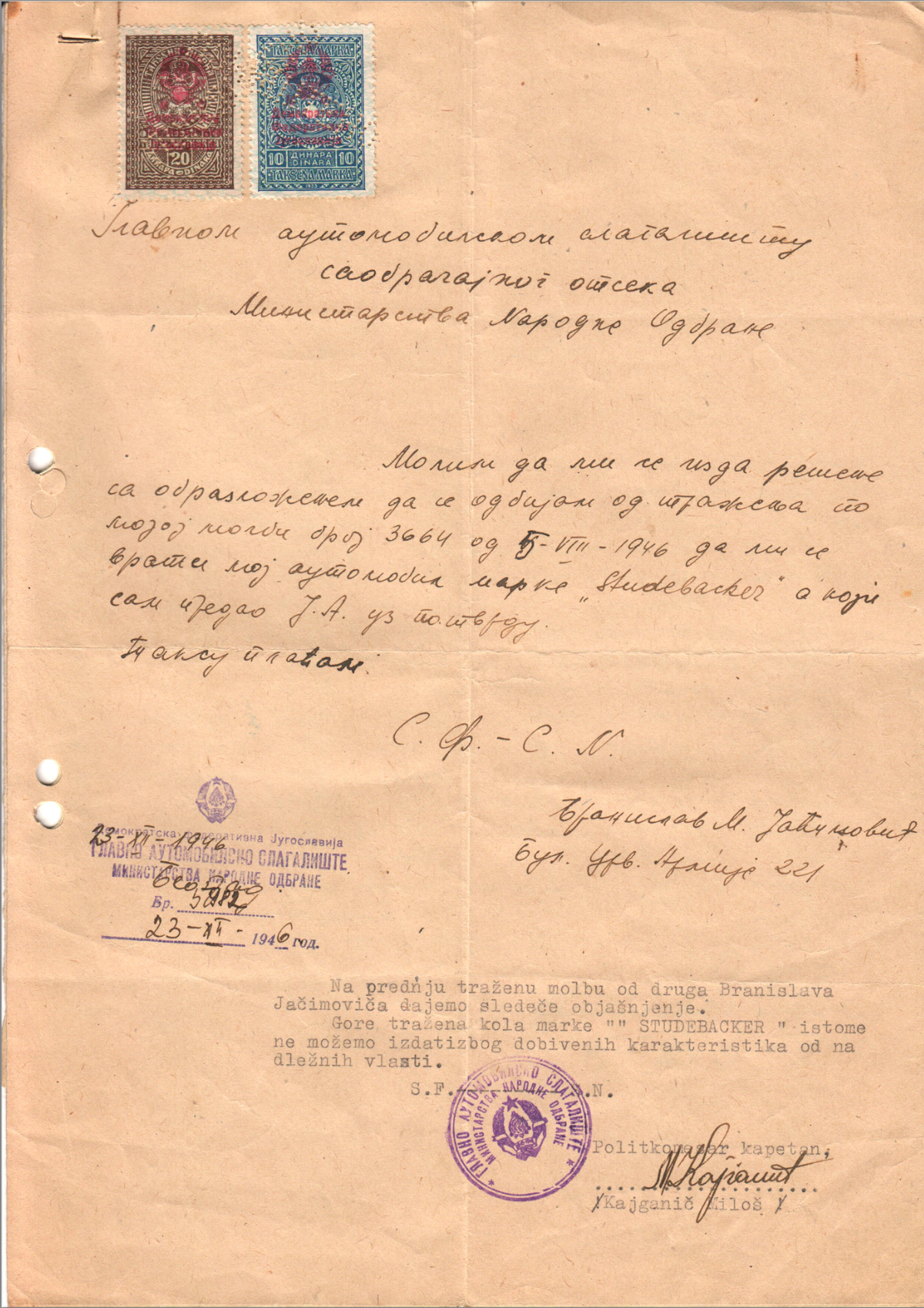

In the first years of the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, he repeatedly tried to get it back. He wrote to various state institutions asking for information about its possible return.

Instead, the new authorities labelled him as a person of ‘non-desirable characteristics’. Due to his privileged past, he simply didn’t fit in to the new narrative of the communist state.

He had become a non-person in his own country.

As I read the words the communist authorities used to tell Branko of his fate, I can’t help but notice the sign-off.

“Smrt fasismu - sloboda narodu!”, they wrote.

Death to fascism, freedom to the people!

Very interesting story about Marija's relatives. I wonder what happened next.